- Gerardo Lizardi

- BBC News World

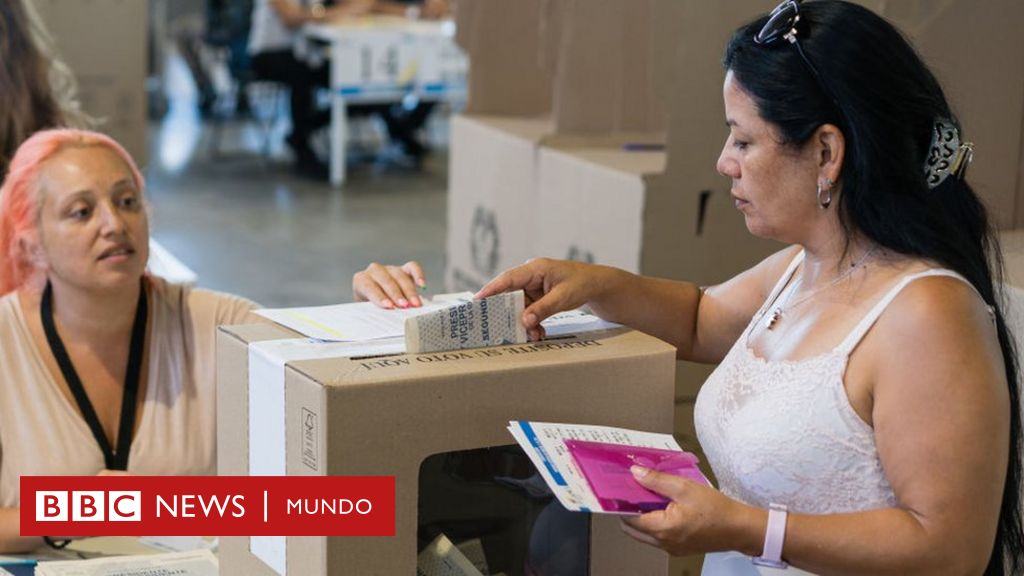

image source, Good pictures

Forget for a moment the much-talked-about polarization: 2022 showed the importance of the political center across America.

The news comes from polls in countries where conflict has escalated in recent times.

In elections this year in Brazil and Colombia, two of the three largest Latin American democracies, centrist voters were decisive.

Although left-wing candidates such as Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva and Gustavo Pedro won in both countries, they won. Appeals to curb against competitors deemed too extremist.

In Chile, they voted widely against a change in the constitution that experts say is considered too radical and unrepresentative of the country’s full range of political opinion.

Even in the US midterm elections in November, the Moderate politicians beat candidates on controversial and radical positions Former President Donald Trump supported him in key states.

“There is dissatisfaction with traditional politics, but at the same time people are not ready to go to extremes,” says Michael Schifter, former head of the Inter-American Dialogue, a Washington-based center for hemispheric analysis, in a conversation with BBC Mundo.

“From the Center”

Polls in Latin America place between 40% and 50% of the region’s population in the political center, with the rest leaning left or right.

This panorama has remained unchanged despite the decline of centrist parties and candidates in many countries in the region in recent years.

“The population is at the center, but it’s missing the political parties that represent it,” observes Shifter, a professor of Latin American studies at Georgetown University. “In Brazil, Colombia and Chile, people no longer identify with traditional center-left or center-right parties.”

image source, EPA

Facing elections this year, Lula aligned himself with his former rival, Geraldo Alcmin.

Faced with this event, Lula also bet on building coalitions beyond his Workers’ Party (PT, left), former center-right rival Geraldo Alcmin was their vice-presidential candidate to defeat right-wing President Jair Bolsonaro.

In the runoff in October, Lula won the support of centrist candidates who came in third and fourth, and former presidents such as social democrat Fernando Henrique Cardoso, who viewed Bolsonaro as a threat to democracy.

All of this was crucial for voters in the center to tip the balance in favor of Lula, who defeated Bolsonaro by a narrow margin (50.9% vs. 49.1%) and is poised to return to the presidency on January 1. He practiced from 2003 to 2011.

“Lula was never an extremist in the strict sense of the word. He was and is a man who made mistakes,” former Uruguayan President Jose Mujica told BBC Mundo on the night his friend was re-elected Brazil’s president.

In Colombia, a former guerrilla and economist Pedro became the first left-wing president in the country’s history In his third attempt and four years after a miserly defeat in the previous elections.

image source, Good pictures

Gustavo Pedro was elected president of Colombia in his third attempt, after a runoff.

And for that He looked at the center: He moderated his speech, created a coalition of alternative forces in the face of the crisis of the traditional political class, promised to avoid the trend of neighboring Venezuela (whose president, Nicolás Maduro, “connected with politics. Death”) and he expected to name the centrist José Antonio Ocampo as finance minister.

So Bogotá’s former mayor collected 2.7 million more votes than in the first round to defeat right-wing Rodolfo Hernández in June’s polls, whom many considered more unpredictable and less ready to govern than his rival.

The story has often repeated itself in the region since many countries regained democracy some 35 years ago.

“There have been more than 100 elections since the transition in Latin America, and if one looks at all of them, one understands that there is always a need for both the right and the left, which are really polarizing and carry the issues. The political center must be chosen,” says Marta Lagos, director of the Latinobarometer regional survey.

“They got the center’s approval because they became less serious,” Lagos tells BBC Mundo.

A volatile vote

The recently worsening crisis of representation in Latin America has also opened up space for governanceOutsidersAbout politics.

This was evident in the continent’s other election this year: in Costa Rica, the economist Rodrigo Chavez He was elected president with a speech in April Installation resistance Although he was almost unknown in his country’s politics.

image source, Good pictures

Rodrigo Chávez became president of Costa Rica with an ‘anti-establishment’ speech.

The situation across the region is favorable for the emergence of populists “disguised as centrists and moderates,” Lagos warns, adding that the collapse of party structures has left a more volatile electorate that even pollsters find difficult to predict.

“Earlier, it was possible to identify which side the center was on. Now that doesn’t happen because the center is no longer looking for an ideological or value issue, but solutions to problems,” he says.

And the voters’ patience with the rulers also seems to have waned.

Indeed, in 2022 the regime continued in Latin America Cycle in power. Of the 14 free presidential elections held in the region since 2019, there has been a vote to change the ruling party.

This created a wave of leftist victories in the subcontinent, the duration of which is uncertain.

The unpredictability of Latin American voters was reflected in Chile in September, when 62% of voters rejected the text of a new constitution drawn up by a conference and supported by a leftist president, Gabriel Boric, who took office as a young leader six months ago. A cry for deeper reforms.

image source, Reuters

The Chilean president, Gabriel Boric, promoted the agreement on a new process for constitutional change.

So there were many Boric voters who opposed the constitutional text and the plan was “not for everyone and out of bounds,” says Lagos from Santiago.

Immediately, Boric announced a change of government with the entry of the traditional center-left in his cabinet and asked to start another constitutive process in Congress, where there was already a basic agreement approved by 14 parties.

The goal is to submit the new draft constitution to a ratification vote in November 2023.

Presidential elections are scheduled in three countries in the region next year: Paraguay (April), Guatemala (June) and Argentina (October).

Questions have already arisen: Will the left’s gains continue? Or will a political turn to the right begin?

But one thing seems certain as of now: a quiet wave at the center will be key in the re-election.

Remember you can get updates from BBC News World. Download the latest version of our apps and activate them so you never miss our best content.

“Wannabe web geek. Alcohol expert. Certified introvert. Zombie evangelist. Twitter trailblazer. Communicator. Incurable tv scholar.”

More Stories

5 things you need to know this April 19

Characteristics that make the Aragua train a unique criminal gang in Latin America

Thousands of people evacuated and tsunami warning